Research Techniques for Treasure Hunters

Posted on January 30, 2020 by hcharles

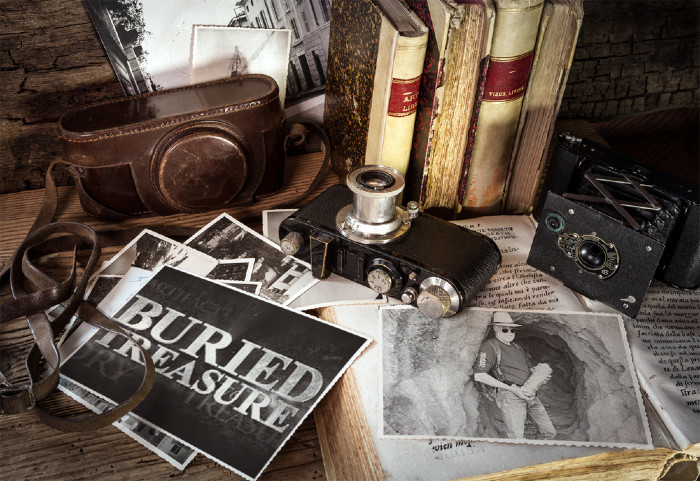

I’m often asked how I manage to find caches of coins and other treasures so easily. What appears to be natural is actually the culmination of hundreds of hours of research that must be done before any metal detecting can be done successfully. Research techniques have evolved with the Internet and are now easier than ever. There is an almost unending list of locations that will never be “hunted out.”

One of the best ways to do research is by talking with others. I’ve learned that most people find the hobby of treasure hunting fascinating. And even though they may not have a metal detector, they have always wanted to be a part of it in some way; nothing has the allure of buried treasure! They’re usually eager to point you in the right direction. Some of the most enjoyable and helpful people you can converse with are older citizens in your community or assisted living. They know where all the events took place, where people used to picnic and of other gathering places that most likely are long forgotten and concealed by years of history. Hunters, loggers, and hikers are also great resources for finding sites to go metal detecting. An experienced hunter, forester, or hiker knows the woods and has most likely come across old foundations and other signs of activity that have been hidden for years by the forest.

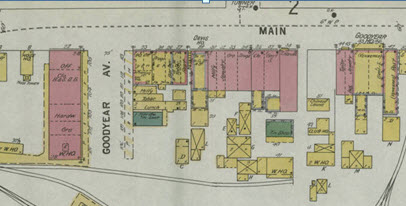

Another great way to find productive metal detecting sites is by using historical maps. Historical maps are much different from the more recent maps you may be used to looking at. What we are looking for are Platt maps or plot plans. Some of the better maps of the last two centuries, Sanborn and Beers Maps contain very detailed information. Some maps will show where structures stood and information on the property owners. These old maps will even have structures labeled with the purpose they served. If you are lucky enough to come across historic maps that are very well detailed, you won’t need much more research to find metal detecting sites. Using old maps has always been my preferred way of locating potential metal detecting sites, especially ghost towns.

Last but not least, using historical documentation to find metal detecting sites is a traditional form of research. This type of research is the most time consuming but can be the most interesting. There are many places that you can find rare historical documents that will help you locate new metal detecting sites. Be sure to search the archives of;

- Small Town Libraries

- Court Houses

- Borough Buildings

- Historical Societies

- Genealogical Centers

- University Archives

- Flea Markets / Antique Shops

- Garage Sales

These are just a hand full of places where you can find good research material. Some documents that you should be looking for include historical books, old newspapers, journals and diaries and old atlases. Old newspapers will tell of the events that took place in the past; deaths, train wrecks, fires, boat sinking’s, bank robberies. Many libraries keep a collection of local newspapers on microfilm that usually goes back many, many years. Historic journals are also excellent research tools; they are firsthand accounts of events and daily life in a particular era and area. Local history books are always recommended for reading. An excellent local history book will often give a view of events not covered in broader histories. Any material that has documented the history of a specific area should be examined for the possibility of locating a productive spot to go metal detecting.

The internet brings a wealth of information to our finger tips. All we have to do is point, click and grab it. I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below or send me an email; and do me a favor, if this article was helpful please share it on facebook or twitter that way I’ll be able to keep bringing you useful information to make more and better metal detecting finds.

Free Software for ARCHAEOLOGISTS & Treasure Hunters

Posted on January 30, 2020 by hcharles

I often get asked by students, friends and colleagues about software solutions for a variety of tasks that treasure hunters do in their daily work routine. Things like mapping dispersion patterns, site documentation etc. Since I’m asked about this so frequently, I thought it would be a good idea to compile a list of my personal recommendations for these requests and share it here. I’ll add more resources as time permits.

Win-BASP

A Windows-based version of the enormously useful BASP program, by Irwin Scollar, including more than 60 functions for seriation, clustering, correspondance analysis, and other tools for archaeologists. http://www.uni-koeln.de/~al001/basp.html

The Harris Matrix

The classic statistical method for diagramming stratigraphic sequences; this

site is intended to “provide an international focal point for information

and discussion.”

PitCalc

While it’s standard archaeological practice to work in square holes, sometimes it’s simply not possible. PitCalc is an ancient (well, 20 years old) computer program brought back to java life to help us out in those situations. http://www.pitcalc.com/

Ox-Cal

By Christopher Bronk Ramsay of Oxford, a program to provide radiocarbon calibration and analysis of archaeological and environmental stratigraphy. http://c14.arch.ox.ac.uk/embed.php?File=oxcal.html

ArchEd

The ArchEd Program is a tool for drawing Harris matrices which are used in archaeology. Beside its ability to edit such drawings it also contains an automatic drawing feature which redraws a given graph nicely. A similar program was developed at the Amt für Bodendenkmalpflege in Bonn in 1990. While this older program runs on DOS – systems and uses the keyboard as input device, ArchEd runs with Win2000, XP or WinNT and can also use a mouse as input device.

You can find more free software HERE http://archaeologicaltraces.org/index.php?option=com_weblinks&view=category&id=51&Itemid=58

The internet brings a wealth of information to our finger tips. All we have to do is point, click and grab it. I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below or send me an email; and do me a favor, if this article was helpful please share it on facebook or twitter that way I’ll be able to keep bringing you useful information to make more and better metal detecting finds.

Conducting Historical Research to Find Virgin Metal Detecting Sites

Posted on January 30, 2020 by hcharles

by H.Charles Beil

Using historical maps, aerial photographs, field examinations, title searches, and archived and published documents, treasure hunters and historians trace the background of important sites. These include public and private lands, stagecoach trails, roadways, Indian reservations, water sources, and historic travel corridors.

Online databases have become one of the keys to retrieving information provided by others, who maintain personal databases to organize the information they have collected during their research.

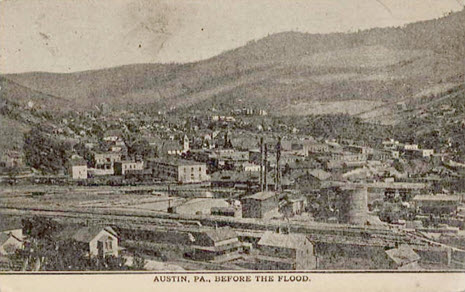

One evening quite late, one of my team from the American Ghost Town Hunters called on the phone to inform me that he had found an undocumented ghost town. The excitement was evident in his voice as he exclaimed “and I did it using those old maps from that website you told me about on the internet”; Thanks. Which old maps website? Now, I was curious. I use a lot of historical map websites in my background research before I actually enter the field to try to locate a town, historic site or treasure cache. I wanted to know which ones. What kind of maps did you use? I queried. He explained how he’d used the digital Sanborn and Beers map database on a Public Library’s website to identify a location in the mountains in Northern Pennsylvania where a village once existed.

The village was now on State land, remote, and probably had never been hunted by a metal detectorist. He printed out a copy of the Beers map from the late 1800s and measured the distance from the village to a stream. Then he measured the distance from the village boundary to the edge of a road; triangulating the village coordinates. Using this information, I organized a trip into the mountains in search of the site. Within a few hours of hiking; success! There among the trees were the foundations of homes that may not have been seen for 150 years. I went on to supervise the documentation, photography and artifact recovery at this site later that year. The finds were significant enough to make it into a magazine.

Any of us interested in heritage conservation, historic preservation or treasure hunting need to be aware of the myriad ways the internet can be used to collect information on the sites that we are seeking. Every day, thousands of historical documents, maps, files, and photographs are uploaded to the internet. These references are making it easier to conduct background research and learn more about our project areas. The problem is, we often want to hit the field before we have fully explored our resources. Putting boots on the ground before conducting thorough research is the bane of all amateur treasure hunters. This generally leads to a wild goose chase for a site that is just no longer there; maybe it was strip mined or to getting caught up in a treasure hoax for something that was never there to begin with.

The difficulty of this process is that these internet sources are often times victims of their own success. As digital information proliferates, a huge pile of data is created that is even more difficult to sift through. In order to make our online historical research more successful, we’ve got to prioritize and establish a process for ourselves; picking the most fruitful yields first and, later, following up with the less necessary sources as time permits. However, it must be noted that nothing that I have found online replaces the quality of the information that is archived in the local historical societies and libraries. It is best to join a large library such as the Carnegie Library in Pittsburgh, University libraries and local historical societies in your area of interest. What online resources can do is to provide quick access to information and expedite the discovery of new places to hunt. This archive is always open for those nights when you just cannot sleep. Here are eight resources I use for efficient online historical research.

- Google Earth – It’s a free atlas of the entire earth.You can digitize polygons, measure distances, calculate UTM coordinates, create your own maps, and zoom in to street level in cities in order to get an excellent idea of what the ground surface looks like today.

- 2) GLO Records – There are two ways any American can become immortal: pay taxes or buy property. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) has digitized its General Land Office (GLO) records and they are now available online. The BLM-GLO website has most of the records for when land west of the Appalachian Mountains was assumed from the public domain for private ownership (Sorry easterners. You probably can’t use this source very often). Private ownership usually indicates when the historical-period began in a given location. The website also has the original surveyor’s notes and maps, which is most helpful for recreating the landscape before it was developed. The only drawback: you have to know the township and range for the parcel you’re looking for.

- Township and Range Grid for Google Earth – In order to solve the aforementioned problem with Google Earth, Earth Point has created a free township and range plugin. You can use this to figure out the township and range information for your project area and use that info to figure out when it was purchased from the Federal government. Note: This only works for places that were surveyed by the Cadastral Land Survey. It won’t be accurate for places that were surveyed before the GLO or that were part of Spanish or Mexican land grants.

- Local Assessor’s Records – (depends on where you’re working)- Like I mentioned earlier, paying taxes is one of the surest ways to become immortal. And the county assessor is always keeping track of who’s paying their taxes. Unfortunately, the quality of information on the assessor’s website varies from place to place. Some counties have ownership and valuation information for the last dozen property owners. Other counties don’t even have this info online. Also, some assessor’s websites require you to know the tax parcel number, which you may not have.

- Google Books -This resource is like a super library of historical references, many of which are available for free. Instead of immediately going down to your local university’s special collections library, you can check out Google Books which usually has dozens of historical references that are past their copyright. A word of warning: You can waste a bunch of time finding and downloading crappy, outdated information on Google Books. Also, this doesn’t replace actually going to special collections and doing real archival research to find documents that haven’t been digitalized.

- Online Digital Archives- Many cities, counties, and states have online digital repositories that you should check out before you go out to the field. Some good examples include the City of Tucson’s Historic Properties Map , the Arizona Memory Project , and the Washington State Digital Archives . The Seattle Public Library and many other repositories offer free access to their Digital Archives, which includes almost every Sanborn map in the United States! Check out this PDF list of Sanborn Maps <https://geo-search.com/services/historical-products-services/> created by Scott Davis of GeoSearch or http://www.libraries.psu.edu/psul/digital/sanborn.html

Sometimes you will need a valid library card and a reciprocal agreement between your local library and these online libraries.

- Library Special Collections What’s better than looking at digital copies of historical books and documents? Perusing real historical books at universities and public libraries. Whenever possible, I allow at least half a day to look at references at a local university or public library’s special collections. Why do I consider this a means of online research? Because you have to spend time online looking up the references you need. This is best done before you visit the repository so you are not wasting time fumbling with books that will not suit your purpose. However, archival research at special collections isn’t for everyone. It can be boring and tedious. And it takes some planning and preparation beforehand. You need to know the hours of operation, rules for proper conduct, and prices; yes, some archives charge by the hour and ALL charge for copies and scans. This is one way that libraries earn money; somebody has to pay the librarians. You also need to be intimately familiar with the repository’s copyright rules and prices for re-publishing archived images and information. It’s also an excellent idea to call before you go and POLITELY talk to the archivists. Ask them to set aside materials for you and schedule a time to look at them. These folks are generally very busy and under staffed and may take offense if you just drop in and expect them to drop everything that they were working on to help you.

- Historical Photographs – A picture speaks a thousand words; as the saying goes. But where do we find those historic images; in the digital archives of course. http://www.whatwasthere.com

These eight resources are by no means the only historical data sources available on the internet. Whenever I’m the one doing this research, I start with Google Earth (with the township and range plugin), go to the BLM-GLO records, and then move on to Google Books. I also check out the digital Sanborns, Beers and Railroad Maps. If I have a whole day for online archival work, I’ll also check out the county assessor’s records and see what the local library has in special collections. Maybe there’ll be something worth going down to the library to look at. If you’re willing to spend money, there are even more resources and a bunch of apps. You can also pay someone else to do the research if the site that you are looking for appears to be really worthwhile.

The internet brings a wealth of information to our finger tips. All we have to do is point, click and grab it. I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below or send me an email; and do me a favor, if this article was helpful please share it on facebook or twitter that way I’ll be able to keep bringing you useful information to make more and better metal detecting finds.

How Rip Van Winkle Effects Treasure Hunting

Posted on January 29, 2020 by hcharles

H.Charles Beil Historical Archaeologist & Treasure Hunter

In Washington Irving’s story Rip Van Winkle goes to sleep and wakes some 20 years later. He learns that the men he met in the mountains are rumored to be the ghosts of Henry Hudson’s crew, which had vanished long ago. He finds that he has been away from his Catskill village for at least twenty years.

Now, imagine if you will, the strange happenings in America in 1752 where everyone went to sleep and woke up nearly 2 weeks later.

A strange phenomenon swept America. If you were living 265 years ago you would have gone to bed on September 2nd and woke up on September 14th.

How could this be?

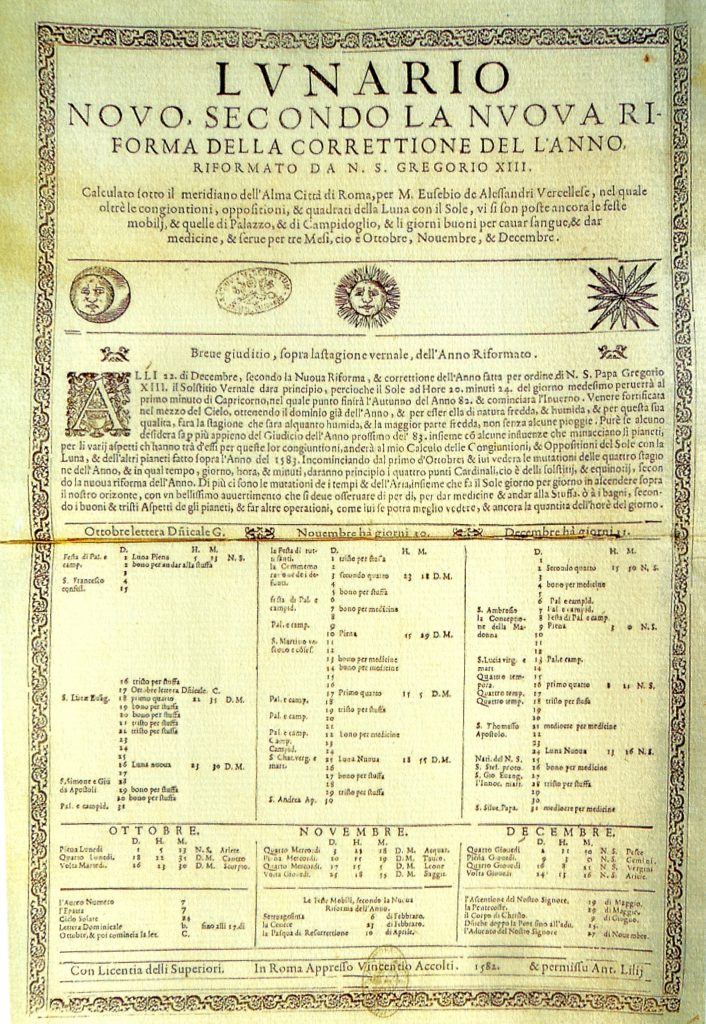

Eleven days had been effectively skipped over as part of the parliamentary measure that implemented the Gregorian calendar, aligning Britain and its overseas possessions with the rest of Western Europe.

The problem as it turned out was the Julian calendar. It didn’t calculate leap years very well and was putting more in than was required. So a new calendar system that did the calculations correctly was proposed. Instead of leap years occurring every four years, they would occur every four years except for years ending in 00 like 1300, 1400, 1500 and so on. This was actually too large a correction, so every four hundred years the new calendar would skip the skip…. meaning that when the century was divisible by 4, the leap year would not be skipped.

Today, Americans are used to a calendar with a “year” based the earth’s rotation around the sun, with “months” having no relationship to the cycles of the moon and New Years Day falling on January 1. However, that system was not adopted in England and its colonies until 1752.

The changes implemented that year have created challenges for historians and genealogists working with early colonial records, since it is sometimes hard to determine whether information was entered according to the then-current English calendar or the “New Style” calendar we use today.

To get the calendar back in sync with astronomical events like the vernal equinox or the winter solstice, a number of days were dropped.

The papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, decreed that 10 days be dropped when switching to the Gregorian Calendar. However, the later the switch occurred, the more days had to be omitted. Therefore when we adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752 we needed to drop 11 days.

This created short months with only 18 days and odd dates like February 30 during the year of the changeover.

In North America the month of September 1752 was exceptionally short skipping 11 days.

The Julian Calendar

In 45 B.C., Julius Caesar ordered a calendar consisting of twelve months based on a solar year. This calendar employed a cycle of three years of 365 days, followed by a year of 366 days (leap year). When first implemented, the “Julian Calendar” also moved the beginning of the year from March 1 to January 1. However, following the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, the new year was gradually realigned to coincide with Christian festivals until by the seventh century, Christmas Day marked the beginning of the new year in many countries.

By the ninth century, parts of southern Europe began observing first day of the new year on March 25 to coincide with Annunciation Day (the church holiday nine months prior to Christmas celebrating the Angel Gabriel’s revelation to the Virgin Mary that she was to be the mother of the Messiah). The last day of the year was March 24. However, England did not adopt this change in the beginning of the new year until late in the twelfth century.

Because the year began in March, records referring to the “first month” pertain to March; to the second month pertain to April, etc., so that “the 19th of the 12th month” would be February 19. In fact, in Latin, September means seventh month, October means eighth month, November means ninth month, and December means tenth month. Use of numbers, rather than names, of months was especially prevalent in Quaker records.

The Gregorian Calendar

During the Middle Ages, it began to became apparent that the Julian leap year formula had overcompensated for the actual length of a solar year, having added an extra day every 128 years. However, no adjustments were made to compensate. By 1582, seasonal equinoxes were falling 10 days “too early,” and some church holidays, such as Easter, did not always fall in the proper seasons. In that year, Pope Gregory XIII authorized, and most Roman Catholic countries adopted, the “Gregorian” or “New Style” Calendar.” As part of the change, ten days were dropped from the month of October, and the formula for determining leap years was revised so that only years divisible by 400 (e.g., 1600, 2000) at the end of a century would be leap years. January 1 was established as the first day of the new year. Protestant countries, including England and its colonies, not recognizing the authority of the Pope, continued to use the Julian Calendar.

Double Dating

Between 1582 and 1752, not only were two calendars in use in Europe (and in European colonies), but two different starts of the year were in use in England. Although the “Legal” year began on March 25, the use of the Gregorian calendar by other European countries led to January 1 becoming commonly celebrated as “New Year’s Day” and given as the first day of the year in almanacs.

To avoid misinterpretation, both the “Old Style” and “New Style” year was often used in English and colonial records for dates falling between the new New Year (January 1) and old New Year (March 25), a system known as “double dating.” Such dates are usually identified by a slash mark [/] breaking the “Old Style” and “New Style” year, for example, March 19, 1631/2. Occasionally, writers would express the double date with a hyphen, for example, March 19, 1631-32. In general, double dating was more common in civil than church and ecclesiastical records.

Changes of 1752

In accordance with a 1750 act of Parliament, England and its colonies changed calendars in 1752. By that time, the discrepancy between a solar year and the Julian Calendar had grown by an additional day, so that the calendar used in England and its colonies was 11 days out-of-sync with the Gregorian Calendar in use in most other parts of Europe.

England’s calendar change included three major components. The Julian Calendar was replaced by the Gregorian Calendar, changing the formula for calculating leap years. The beginning of the legal new year was moved from March 25 to January 1. Finally, 11 days were dropped from the month of September 1752.

The changeover involved a series of steps:

- December 31, 1750 was followed by January 1, 1750 (under the “Old Style” calendar, December was the 10th month and January the 11th)

- March 24, 1750 was followed by March 25, 1751 (March 25 was the first day of the “Old Style” year)

- December 31, 1751 was followed by January 1, 1752 (the switch from March 25 to January 1 as the first day of the year)

- September 2, 1752 was followed by September 14, 1752 (drop of 11 days to conform to the Gregorian calendar)

Which Calendar Is It?

Out of context, it is sometimes hard to determine whether information in colonial records was entered “Old Style” or “New Style.” Some examples:

In the Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, “A Corte at New Towne [Hartford] 27 Decr. 1636” is immediately followed by a court held “21 Febr. 1636,” which is followed, in turn, by “A Cort att Hartford, Mrch 28th, 1637”. Although it may first appear that the February session was entered out of sequence, the arrangement is actually correct. Under the “Old Style” calendar and legal new year, 1636 began on March 25. December 1636 was followed by January 1636 and February 1636, and 1636 continued through March 24.

The “Warwick Patent” is dated the “Nineteenth day of March in the Seventh/ yeare of ye reigne of our Sovergne Lord Charles by ye grace of God/ Kinge of England Scotland Ffrance and/ Ireland defender of ye ffaith &c Anno Dom/ 1631.” Although not double dated, the historical context indicates that the date as recorded was “Old Style.” If double dated, it would have been recorded as March 19, 1631/2; if recorded “New Style,” it would be March 19, 1632.

John and Joane Carrington, accused of “familliarity with Sathan the great Enemye of God and mankinde” were indicted by Connecticut’s Particular Court on “6 March 1650/1.” In his “diary” or notebook, Matthew Grant records that they were executed “mar. 19.50.” Although Grant did not employ the double date, had he done so it would have been recorded as March 19, 1650/1.

Although current historical scholarship calls for retention of Old Style dates in transcriptions, historians and genealogists need to be aware that some people living at the time converted the date of an event, such as a birthday, from Old Style to New Style. George Washington, for example, was born on February 11, 1731 under the Julian Calendar, but afterwards recognized the date February 22, 1732 to reflect the Gregorian Calendar.

What this means to the treasure hunter who is researching a shipwreck during this period is that the ship might be recorded as leaving port on a particular date in the old style but recorded as sinking in the new style. If we are calculating the distance that it traveled per day our calculations will be off by approximately 12 days and we will be searching miles from where the ship most likely sunk. We need to be sure that we are reconciling our dates when using them to to put an X on the map!

The internet brings a wealth of information to our finger tips. All we have to do is point, click and grab it. I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below or send me an email; and do me a favor, if this article was helpful please share it on facebook or twitter that way I’ll be able to keep bringing you useful information to make more and better metal detecting finds.

Recent Posts

Archives

About This Site

The Treasureman Site is about the fabulous hidden treasures of H.Charles Beil.

Copyright © 2026 · All Rights Reserved ·

Theme: Natural Lite by Organic Themes · RSS Feed

Recent Comments