How Rip Van Winkle Effects Treasure Hunting

Posted on January 29, 2020 by hcharles

H.Charles Beil Historical Archaeologist & Treasure Hunter

In Washington Irving’s story Rip Van Winkle goes to sleep and wakes some 20 years later. He learns that the men he met in the mountains are rumored to be the ghosts of Henry Hudson’s crew, which had vanished long ago. He finds that he has been away from his Catskill village for at least twenty years.

Now, imagine if you will, the strange happenings in America in 1752 where everyone went to sleep and woke up nearly 2 weeks later.

A strange phenomenon swept America. If you were living 265 years ago you would have gone to bed on September 2nd and woke up on September 14th.

How could this be?

Eleven days had been effectively skipped over as part of the parliamentary measure that implemented the Gregorian calendar, aligning Britain and its overseas possessions with the rest of Western Europe.

The problem as it turned out was the Julian calendar. It didn’t calculate leap years very well and was putting more in than was required. So a new calendar system that did the calculations correctly was proposed. Instead of leap years occurring every four years, they would occur every four years except for years ending in 00 like 1300, 1400, 1500 and so on. This was actually too large a correction, so every four hundred years the new calendar would skip the skip…. meaning that when the century was divisible by 4, the leap year would not be skipped.

Today, Americans are used to a calendar with a “year” based the earth’s rotation around the sun, with “months” having no relationship to the cycles of the moon and New Years Day falling on January 1. However, that system was not adopted in England and its colonies until 1752.

The changes implemented that year have created challenges for historians and genealogists working with early colonial records, since it is sometimes hard to determine whether information was entered according to the then-current English calendar or the “New Style” calendar we use today.

To get the calendar back in sync with astronomical events like the vernal equinox or the winter solstice, a number of days were dropped.

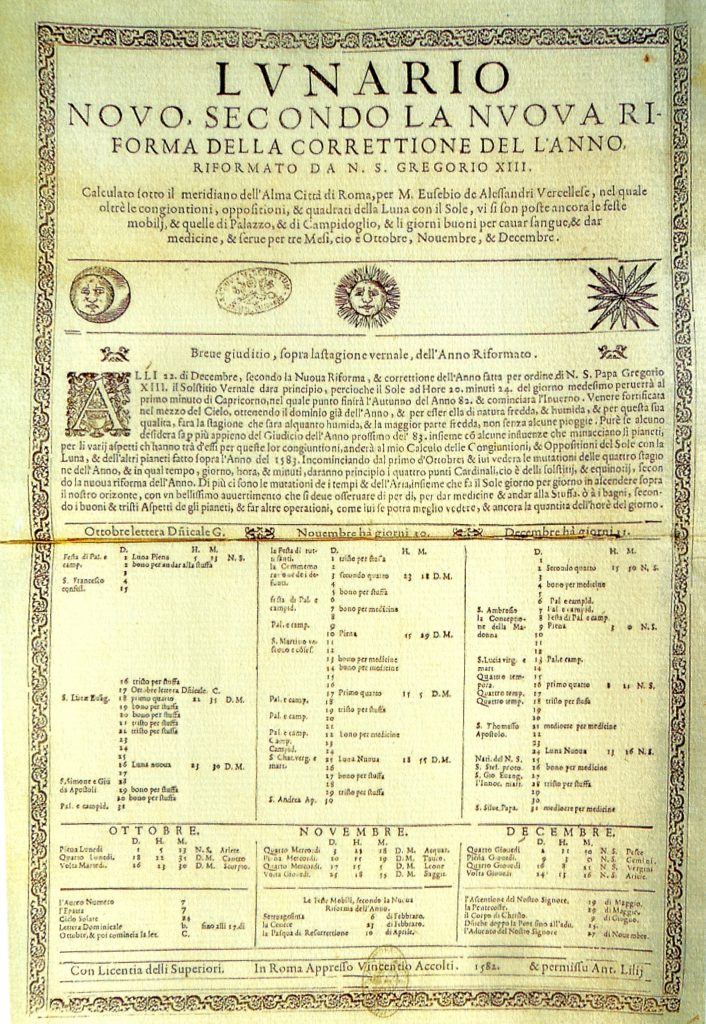

The papal bull issued by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582, decreed that 10 days be dropped when switching to the Gregorian Calendar. However, the later the switch occurred, the more days had to be omitted. Therefore when we adopted the Gregorian Calendar in 1752 we needed to drop 11 days.

This created short months with only 18 days and odd dates like February 30 during the year of the changeover.

In North America the month of September 1752 was exceptionally short skipping 11 days.

The Julian Calendar

In 45 B.C., Julius Caesar ordered a calendar consisting of twelve months based on a solar year. This calendar employed a cycle of three years of 365 days, followed by a year of 366 days (leap year). When first implemented, the “Julian Calendar” also moved the beginning of the year from March 1 to January 1. However, following the fall of the Roman Empire in the fifth century, the new year was gradually realigned to coincide with Christian festivals until by the seventh century, Christmas Day marked the beginning of the new year in many countries.

By the ninth century, parts of southern Europe began observing first day of the new year on March 25 to coincide with Annunciation Day (the church holiday nine months prior to Christmas celebrating the Angel Gabriel’s revelation to the Virgin Mary that she was to be the mother of the Messiah). The last day of the year was March 24. However, England did not adopt this change in the beginning of the new year until late in the twelfth century.

Because the year began in March, records referring to the “first month” pertain to March; to the second month pertain to April, etc., so that “the 19th of the 12th month” would be February 19. In fact, in Latin, September means seventh month, October means eighth month, November means ninth month, and December means tenth month. Use of numbers, rather than names, of months was especially prevalent in Quaker records.

The Gregorian Calendar

During the Middle Ages, it began to became apparent that the Julian leap year formula had overcompensated for the actual length of a solar year, having added an extra day every 128 years. However, no adjustments were made to compensate. By 1582, seasonal equinoxes were falling 10 days “too early,” and some church holidays, such as Easter, did not always fall in the proper seasons. In that year, Pope Gregory XIII authorized, and most Roman Catholic countries adopted, the “Gregorian” or “New Style” Calendar.” As part of the change, ten days were dropped from the month of October, and the formula for determining leap years was revised so that only years divisible by 400 (e.g., 1600, 2000) at the end of a century would be leap years. January 1 was established as the first day of the new year. Protestant countries, including England and its colonies, not recognizing the authority of the Pope, continued to use the Julian Calendar.

Double Dating

Between 1582 and 1752, not only were two calendars in use in Europe (and in European colonies), but two different starts of the year were in use in England. Although the “Legal” year began on March 25, the use of the Gregorian calendar by other European countries led to January 1 becoming commonly celebrated as “New Year’s Day” and given as the first day of the year in almanacs.

To avoid misinterpretation, both the “Old Style” and “New Style” year was often used in English and colonial records for dates falling between the new New Year (January 1) and old New Year (March 25), a system known as “double dating.” Such dates are usually identified by a slash mark [/] breaking the “Old Style” and “New Style” year, for example, March 19, 1631/2. Occasionally, writers would express the double date with a hyphen, for example, March 19, 1631-32. In general, double dating was more common in civil than church and ecclesiastical records.

Changes of 1752

In accordance with a 1750 act of Parliament, England and its colonies changed calendars in 1752. By that time, the discrepancy between a solar year and the Julian Calendar had grown by an additional day, so that the calendar used in England and its colonies was 11 days out-of-sync with the Gregorian Calendar in use in most other parts of Europe.

England’s calendar change included three major components. The Julian Calendar was replaced by the Gregorian Calendar, changing the formula for calculating leap years. The beginning of the legal new year was moved from March 25 to January 1. Finally, 11 days were dropped from the month of September 1752.

The changeover involved a series of steps:

- December 31, 1750 was followed by January 1, 1750 (under the “Old Style” calendar, December was the 10th month and January the 11th)

- March 24, 1750 was followed by March 25, 1751 (March 25 was the first day of the “Old Style” year)

- December 31, 1751 was followed by January 1, 1752 (the switch from March 25 to January 1 as the first day of the year)

- September 2, 1752 was followed by September 14, 1752 (drop of 11 days to conform to the Gregorian calendar)

Which Calendar Is It?

Out of context, it is sometimes hard to determine whether information in colonial records was entered “Old Style” or “New Style.” Some examples:

In the Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut, “A Corte at New Towne [Hartford] 27 Decr. 1636” is immediately followed by a court held “21 Febr. 1636,” which is followed, in turn, by “A Cort att Hartford, Mrch 28th, 1637”. Although it may first appear that the February session was entered out of sequence, the arrangement is actually correct. Under the “Old Style” calendar and legal new year, 1636 began on March 25. December 1636 was followed by January 1636 and February 1636, and 1636 continued through March 24.

The “Warwick Patent” is dated the “Nineteenth day of March in the Seventh/ yeare of ye reigne of our Sovergne Lord Charles by ye grace of God/ Kinge of England Scotland Ffrance and/ Ireland defender of ye ffaith &c Anno Dom/ 1631.” Although not double dated, the historical context indicates that the date as recorded was “Old Style.” If double dated, it would have been recorded as March 19, 1631/2; if recorded “New Style,” it would be March 19, 1632.

John and Joane Carrington, accused of “familliarity with Sathan the great Enemye of God and mankinde” were indicted by Connecticut’s Particular Court on “6 March 1650/1.” In his “diary” or notebook, Matthew Grant records that they were executed “mar. 19.50.” Although Grant did not employ the double date, had he done so it would have been recorded as March 19, 1650/1.

Although current historical scholarship calls for retention of Old Style dates in transcriptions, historians and genealogists need to be aware that some people living at the time converted the date of an event, such as a birthday, from Old Style to New Style. George Washington, for example, was born on February 11, 1731 under the Julian Calendar, but afterwards recognized the date February 22, 1732 to reflect the Gregorian Calendar.

What this means to the treasure hunter who is researching a shipwreck during this period is that the ship might be recorded as leaving port on a particular date in the old style but recorded as sinking in the new style. If we are calculating the distance that it traveled per day our calculations will be off by approximately 12 days and we will be searching miles from where the ship most likely sunk. We need to be sure that we are reconciling our dates when using them to to put an X on the map!

The internet brings a wealth of information to our finger tips. All we have to do is point, click and grab it. I would really love to hear from you. If you have any questions or comments, please post them below or send me an email; and do me a favor, if this article was helpful please share it on facebook or twitter that way I’ll be able to keep bringing you useful information to make more and better metal detecting finds.

Category: Ghost Towns, Metal Detecting, Research, Treasure Hunting, Uncategorized Tags: H Charles Beil, lost treasure, metal detecting, treasure hunting

Recent Posts

Archives

About This Site

The Treasureman Site is about the fabulous hidden treasures of H.Charles Beil.

Copyright © 2025 · All Rights Reserved ·

Theme: Natural Lite by Organic Themes · RSS Feed

Recent Comments